Cartographic Treasures in the Records of the Supreme Court of the United States

“It is interesting that these maps that are now seen as ‘an icon of gorgeous cartography’ weren’t part of the canon until long after they were made . . . there might be countless other gorgeous maps buried in government reports that we don’t know about.”

— Bill Rankin1

As many government information librarians know, maps can be found in official publications and documents from just about every type of government agency but as often as we come across them in the expected places there are just as many sources, as historian and cartographer Bill Rankin suggests, of sometimes-stunning maps, plats and images that remain largely unexplored. Often providing crucial context, these maps are usually overlooked once an issue has passed from the news, as they are subordinate to the document or report that they were created to support. This article will introduce one of these unexplored resources: the Records and Briefs of the Supreme Court of the United States. A familiar resource for information about the Supreme Court, the records and briefs are rarely thought of as a resource for cartographic or other visual information yet the historical records and briefs abound with this material.2

By way of introduction, this article will briefly consider how maps and other images have been used—or not used—by the Supreme Court,3 describe the library and the collection, and review a current project within the library to improve access to this graphic material for Supreme Court researchers, while providing a few sample images along the way.

Maps and Images at the Supreme Court of the United States

Law and geography often go hand-in-hand. As individual citizens, we interact with the law daily and usually without even considering the spatial context in which it operates. Laws tell us where we can drive, where we can and cannot build, where we can smoke, and where we can and cannot live. Laws can even reach into as intimate a space as where we can worship or which bathroom can be used and by whom. From the early English Law of the Forest to modern laws of war and through to the most recent travel restrictions and “stay-at-home” orders issued during the COVID-19 pandemic, law and place are intertwined.4 Geography and maps, according to historian Susan Schulten, are essential to the administration of government.5 While a scholarly focus on the ways that geography and law intersect has slowly gained prominence in academia, the connection between law and geography has always been present.

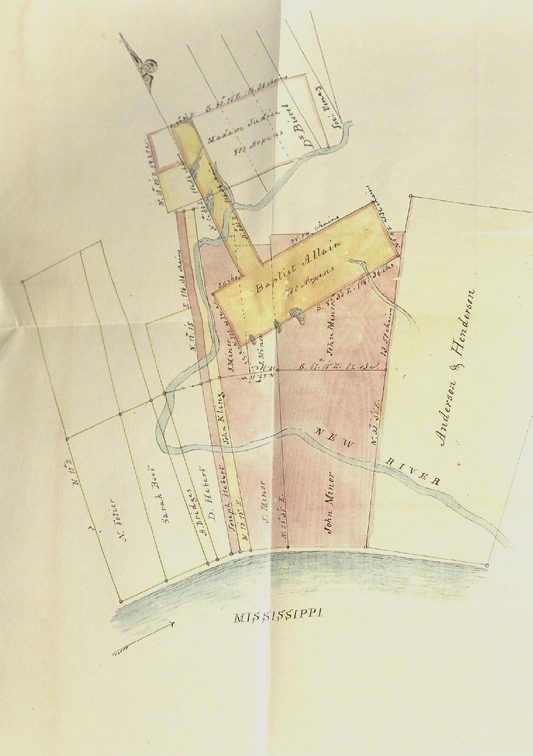

Perhaps reflecting this wider connection, illustrative material, especially cartographic images, have been a part of the Court’s working resources from its earliest history. Some of the Court’s most famous early cases are ones in which geography and maps played an important role. These include New York v. Connecticut, 4 U.S. 1 (1799), Fletcher v. Peck, 10 US 87 (1810) and Barron v. Baltimore, 32 US 243 (1833). The Library’s onsite collection of Records and Briefs begins in 1832 and these first volumes include hundreds of hand drawn maps such as the claim by John Minor and others below that are essential to understanding the geography and the context of the cases.

Despite this rich historical connection, courts generally have not always valued the presence of maps as prima facia evidence.6 Although the Supreme Court has long received maps and other images with the lower court record, an attorney appearing for oral arguments was usually discouraged from trying to present any cartographic material at argument. As recorded by former Reporter of Decisions, Charles Henry Butler:

Another of Marshal [John M.] Wright’s stories told how counsel spread out a large map. One of the Justices asked what it was, and counsel replied that it was a bird’s-eye view of the scene where the cause of action arose. Another Justice interposed: “Well, as we are not birds, you can take it away.”7

In spite of this antipathy towards maps, the Court acknowledged the need to have access to all the lower court documentation including any illustrations or maps by issuing one of its first rules specifically addressing illustrative material in 1823:

Rule 31 (1823)

No cause will hereafter be heard until a complete record, containing in itself, without references aliunde, all the papers, exhibits depositions, and other proceedings which are necessary to the hearing in this Court shall be filed.8

More recently and on “rare occasions,” the Court has given permission for attorneys appearing before the Court in patent cases to include in their briefs illustrations “which may be duplicated in such size as is necessary in a separate appendix.” The limits of the Court’s current practice are explained in Supreme Court Practice (11th edition):

In addition, with the permission of the merits clerk, documents that include extensive maps, drawings, tables, or other material that do not lend themselves to printing in the booklet format may also be reproduced by clear photographic means in an 8½- by 11-inch bound volume, if these exceed the printer’s ability to deal with the items using methods such as fold-out pages from a booklet-format appendix.9

As suggested here, while maps and images have been present in the record from early in the nineteenth century, even when presented at Court they do not often make their way into the final published opinion. As noted in the opinion of the Court in the 1854 case of Brooks v. Fiske, Court Reporter Benjamin Howard wrote of the patent illustrations included at argument:

The Reporter finds himself unable to give an intelligible explanation of the arguments of counsel, without introducing engravings, which would be out of place in a law book. [Emphasis added]10

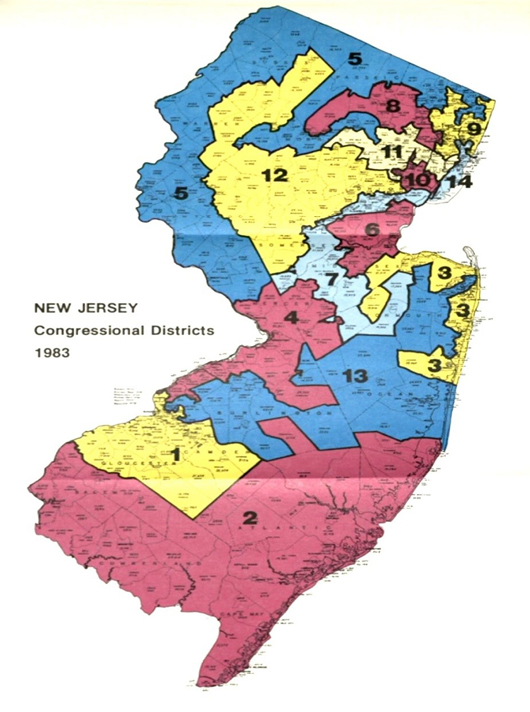

In those instances when the Court included a map, it was often done with some misgivings.11 The late Justice Stevens, in discussing his separate opinion in the Gerrymandering case of Karcher v. Daggett, 462 US 725 (1983) explained that despite the Chief Justice’s reluctance and “because the colored map provided the most persuasive evidence supporting my view of the law, I requested the Court’s Printer to include it in the official report of the case.”12

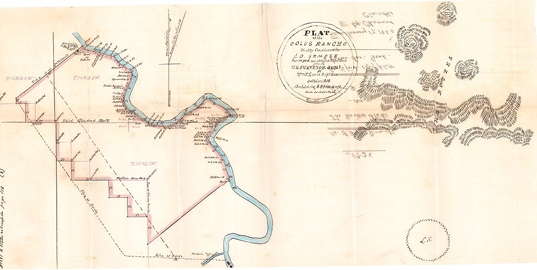

Researchers though will have difficulty finding this unique content as it is mostly absent from the familiar Supreme Court indexing tools and databases.13 Because of the size and makeup of the many maps in the historical records very few of them—most often when they are limited to the standard page size of the brief itself—are included in the Gale-Cengage Making of Modern Law Records and Briefs Collection.14 Nor are larger cartographic images, such as the Colus Rancho plat from the case “United States v. Semple,” shown below included (again with a few exceptions) in the West or Lexis collections of briefs. Our project sought to improve access to this material for our onsite court users.

About the Library

The Supreme Court of the United States Library’s primary mission is to assist the Justices, both active and retired, in fulfilling their constitutional responsibilities by providing them with the best reference and research support in the most efficient, ethical, and economic manner. The Library holds over 600,000 print volumes, 200,000 microform volumes and a wide variety of electronic resources. The collection focuses primarily on Anglo-American law and is rich in United States federal and state primary law, works on constitutional law and history, legal dictionaries, and US government documents acquired both by “riding the jacket” directly and through our participation in the FDLP. Central to the Library’s support of the Court is the Records and Briefs Collection. Containing opinions, briefs, transcripts, lower court records, and oral arguments the collection is the most comprehensive archival set of these materials. It is from this collection that the images described in this article are drawn.

The Records and Briefs Inserts Project at the Supreme Court of the United States Library

The Records and Briefs Inserts project was developed to identify and record the location of each illustration in the documents filed with the Supreme Court regardless of the content of the image. For the purpose of this project, an image is defined as any data, graphic, or text that is included as a separate piece or page in the bound Records and Briefs and that either exceeds or is smaller than the normal page size of the volume. Within the Library, these images are referred to as “inserts” for how they are placed into the bound record. Information that appears as part of a printed page and that conforms to the printed page size of the brief are not included in this project, as those items have generally been included in other commercial databases.

At the Supreme Court of the United States, a conservation project has been underway since 2004 to identify and protect Records and Briefs volumes in deteriorating condition. These volumes are sent to an off-site conservation center and in the course of the conservation work, the images are removed and copied. In addition, an archival quality working copy of the volume is also created. As the images—particularly the oversized items—are often in fragile condition, the originals are removed, treated and returned to the Library to be stored separately. Prior to this project, a brief location guide had been created for the largest oversized maps while the smaller inserts were placed in boxes by size and volume year. This location guide however did not include sufficient information to associate the insert with the case or documents from which it was drawn—only where it was filed. Clearly if the value of metadata for access lay in part in its completeness, our location guide was lacking.15]

In 2016 when staff were asked to locate images by case for a possible display it quickly became evident that the basic location guide would no longer suffice. In response, the Technical Services and Special Collections Department of the Library, which also has responsibility for the Court’s federal depository collection, initiated a project to fully identify and record the location of each insert in both the original Records and Briefs volume and to coordinate that information with the file location.

Since the items included in the existing location guide are limited to those volumes that had conservation work and we needed to create a comprehensive guide for all the inserts, it was decided to start from the first volume and to incorporate whenever possible the existing file location information as part of the new data recordation process.

Although paging through each volume by hand is labor intensive, the process for creating the index content itself is straightforward. Beginning in 1832, with the earliest volumes in the Library’s collection, volumes are removed from the shelf and paged through by hand with the data compiled in an Excel worksheet. After discussing with other library staff it was decided that the spreadsheet finding aid would include year, volume, page number, case name, official and parallel citations, material type, document size and subject. The subjects are created by using Westlaw headnotes or reading the case and applying Library of Congress Subject headings. Information that is not required but provided whenever available includes geographic location, local notes and the original cabinet location. As mentioned above, the map cabinet location is only included for those oversized insets already present in the older location guide. Finally, if the item has not been sent to conservation, a note is made of that as there will be no inserts in the file cabinets and the only copy will be the original on the shelf.

Looking Ahead

In fall of 2019, a review of the full set of ninteenth century volumes was completed. Working with staff from MARCIVE, a complete set of MARC records have been created for this content and the records have been added to the Court’s online catalog. A project to undertake a similar survey of and indexing of the twentieth-century cases along with their maps and other illustrations, placed on hold due to COVID, will get underway in the summer of 2022. Once completed, library staff at the Supreme Court of the United States will be able to provide comprehensive access for our onsite users to these important and overlooked resources.

Acknowledgment

The author thanks the editorial staff of Unbound: A Review of Legal History and Rare Books (AALL) for permission to use portions of an earlier article on this project here (https://www.aallnet.org/lhrbsis/wp-content/uploads/sites/10/2019/10/LHRBSIS-Unbound-Volume-11-Number-2.pdf). I also extend appreciation for my colleague and co-author of the earlier article, Joann Maguire-Chavez, Special Collections / Records and Briefs Librarian, for her support and permission as well.

Notes

- Betty Mason and Greg Miller, All Over the Map: A Cartographic Odyssey (National Geographic Press, 2018), 16.

- Although often described as “foldouts” in digitization projects because the graphic image is usually “inserted” into the record as an exhibit we have retained the use of the word “insert” to describe this content.

- Nothing in this article should be understood to represent the position of the Supreme Court of the United States regarding any of the cases discussed or referenced. Descriptions of the cases whenever provided will be drawn from the published headnotes or “questions presented.”

- The author acknowledges a western bias for the purpose of this intentionally brief introduction and does not mean to convey that other systems of law or world views do not have a similar (or differing) experience regarding the “spatiality” of the law. See generally Irus Braverman et al., The Expanding Spaces of Law: A Timely Legal Geography (Stanford, CA. Stanford Law Books, 2014).

- Susan Schulten, Mapping the Nation: History and Cartography in Nineteenth Century America (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2012), 7.

- “Prima facie evidence: evidence that will establish a fact or sustain a judgment unless contradictory evidence is produced.” Black’s Law Dictionary, 7th ed., Bryan A. Garner, editor in chief (St. Paul, MN: West Group, 1999), 579. For a detailed study of how maps are used as evidence generally, see Hyung K. Lee, “Mapping the Law of Legalizing Maps: The Implications of the Emerging Rule on Map Evidence in International Law,” Pacific Rim Law and Policy Journal 14, no. 1 (January 2005).

- Charles Henry Butler, A Century at the Bar of the Supreme Court of the United States (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1942), 89.

- 21 US V, VI (1823).

- BNA. Supreme Court Practice: Chapter 12. Preparing and Printing the Joint Appendix. Supreme Court Practice 11th edition. at 12.7.

- Brooks v. Fiske. 56 US 212, 214 (1854).

- For a detailed examination of how the Supreme Court of the United States has responded to the presence of images see Hampton Dellinger, “Words are Enough: The Troublesome Use of Photographs, Maps and Other Images in Supreme Court Opinions,” Harvard Law Review 110 (1997), 1754.

- John Paul Stevens, The Making of a Justice: Reflections on My First 94 years (New York: Little Brown and Company, 2019), 193.

- Dellinger, “Words are Enough.”

- Author’s e-mail exchange with project staff from Gale-Cengage (2015). On file with the author.

- Articles that address the challenges presented in creating metadata for digital projects abound. For a recent analysis see Marta Kuzma and Albina Moscicka, “Metadata Evaluation Criteria in Respect to Archival Maps Description: A Systemic Literature Review,” The Electronic Library 38, no. 1 (2020): 1–27.

Image 1. John Minor’s claim. Transcript of Record, 1833, v.2

Image 2. Karcher v. Daggett, 462 US 725 (1983)

Image 3. Plat of the Colus Rancho. Transcript of Record—1864, v.2